The sea lions first visited San Francisco’s Pier 39 thirty years ago, and decided to stay. While the arrangement, in this case, was beneficial for both sides, close contact between wild animals and humans can stir serious issues

In September 1989, several uninvited guests showed up at San Francisco’s Pier 39 – Californian sea lions (Zalophus californianus), who made themselves comfortable on the wharf, basking in the warm sun. The pier, serving fishermen and boat owners under normal circumstances, was undergoing repairs at the time, and the empty jetty was an attractive spot for the marine mammals. The boats later returned, but no effort was made to evict the guests: Only six to ten of them arrived daily at the pier, and there were enough empty jetties for everyone. But soon afterwards, it turned out that this was only the beginning.

More and more sea lions abandoned their former home in the ‘sea lion rocks’ islands facing the city’s western shores and moved into the bay. On January 19, 1990, a large group landed on Pier 39, and, together with its pioneer tenants, now numbered some 150 individuals. And while set as ‘Sea Lion Day,’ this date did not signify the peak of pinniped immigration: The large mammals kept coming, and two months later, numbered more than 400.

No one knows for certain what caused their immigration. Some believe that the October 1989 earth quake in the area, which wreaked havoc in the colony’s former location, sent the sea lions in search of a new home – but, as mentioned earlier, the ‘invasion’ had started some weeks earlier, in September. It is also possible that they simply found the bay’s water more inviting, with its abundance of food and rare presence of great white sharks and orcas, sea lion predators.

Whatever the reason, there they were, requiring boat owners to navigate among wild animals weighing hundreds of kilograms to reach their boats. While they are not particularly aggressive, sea lions can bite if feeling threatened, for example when humans step on them or try to move them out of the way. They also do not exactly qualify for the “best guest award”: Their ceaseless barking can be heard for miles, and the foul smell of fish that they excrete fills the surroundings.

But there were also those who thought that the sea lions’ arrival was cause for celebration. “Our business has doubled since the sea lions came to Pier 39,” an owner of a nearby restaurant told local media in 1991. A place inside the city where wild animals can be seen up close is a rarity, and the pier attracted both tourists and locals who came to do just that – and maybe also have a bite at the same time. The sea lions delivered their end of the bargain. They are playful social animals, and their chasing one another in the water or pushing their friends off the pier into the water, are highly entertaining.

Perhaps not exemplary guests, but certainly a tourist attraction. Sea lions on Pier 39. Photography: Yonat Eshchar.

Leave them be

The municipality turned to the Marine Mammal Center, which is located in nearby Sausalito and treats sick and injured marine mammals, fur seals, elephant seals, and others, in addition to sea lions. “The Center recommended that they leave them be,” said Laura Gill, an employee of the center, who had previously worked at Pier 39, in an interview to the Davidson website. “This is our motto to this day, ‘leave sea lions be’.”

Accepting this suggestion, the municipality decided to evict not the maritime guests but the boats, which were moved to other piers, and, in the spring of 1990, Pier 39 was declared sea lion territory. The Marine Mammal Center sent volunteers to provide visitors with information and instruct them how to observe the animals without bothering them.

As they do every year, the sea lions migrated south in the summer, to their breeding grounds in the Channel Islands of southern California and the Gulf of California in Mexico. But at the end of August, they began returning in even greater numbers than before. Year after year, the sea lions are making Pier 39 their fall and winter home, with some of the males remaining there for the summer, as well. At the same time, many females stay in the breeding grounds all year long, so the Pier 39 residents are mostly males. Their numbers continued to swell, and in peak months they number more than 1,500 members. When I was there, in the first week of September, there were already several dozens.

Thanks to the sea lions’ presence, Pier 39 became one of San Francisco’s favorite attractions. A small tourist center was opened next to it with restaurants, souvenir shops, and even a carousel. The Sea Lion Center at the pier provides information about the guests-turned-residents, and a steady stream of visitors comes to watch. The ‘arrangement’ is beneficial for both parties: The sea lions have gained prime territory, providing safety from predators and ample food, and the city gained another lucrative tourist attraction.

Sea lions replaced the boats on the pier. Pier 39 in San Francisco. Photography: Yonat Eshchar.

Animals in distress

Californian sea lions live along North America’s western coast, from southeast Alaska to Mexico. They are similar to seals but are larger – adult males can reach a weight of close to 400 kilograms. One prominent difference between the two species lies in the ears: True seals have ear cavities only, while sea lions have external ear flaps as well – small auricles that look like skin folds.

In the past, sea lions were hunted and their population shrank, but since 1972, they are protected in the United States under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, and their numbers have grown to several hundreds of thousands. The Marine Mammal Center treats hundreds of them every year, as well as smaller numbers of elephant seals and other mammals. The center’s workers rely on the local populace to contact them when an animal is in distress.

“The public is our eyes and ears,” says the center’s Giancarlo Rulli. “When we are alerted about a potential problem, we come to assess the situation and check whether an animal is sick or injured, or simply came onto the shore to rest and then nothing needs to be done. Every year, we run advertising campaigns to educate people on how to safely observe wild animals.” Evacuating an animal to the center earns the rescuer a unique privilege: Naming it.

Only a small percentage of the animals that arrive at the center, numbering 80-100 annually, are directly compromised by humans. Sometimes, people come too close to the sea lions, hurt them, or drive them away from the beach, but most of the injuries are caused by entanglement in marine debris, mostly plastic.

“Curious animals, such as fur seals or sea lions, tend to get into trouble with marine debris. Plastic and other waste can get caught around their necks or snouts, and lead to rapid decrease in body weight,” says Rulli. “We have developed methods of shooting tranquilizer darts, and then our team can approach the animal and remove the blockage. If a more complicated procedure is required, we bring the animal here, but most of the time it is sufficient to deal with the problem in the field and release the animal back to the ocean.”

Gill says that one of the center’s most important messages for its visitors refers to the use of plastics. “There are so many simple things that people can do to cut down on the single-use plastics that harm our patients. Things such as giving up drinking straws and single-use plastic bags when possible and opting for multiple-use water bottles.”

Plastic endangers lives. A sea lion in California with a bottle in its mouth. Photography: Shutterstock.

Diseases of the deep

Humans also affect sea lion health, and the ocean in general, in indirect ways, by altering the environmental conditions. One example, is the increase of domoic acid (a material secreted by algae) poisoning among sea lions in the last 20 years. This is due to the rising incidence of algal blooms – the rapid reproduction of algae and expansion over large areas. “In the past, we would see domoic acid poisoning outbreaks at the end of the summer and during the fall, but now, we see it throughout the year,” Rulli says. “We don’t know precisely why it happens and we are still studying it.” Two factors are fertilizer runoffs and the increase in water temperature. “Rather than a single factor that is responsible, a combination of factors is at play – none of which none is going to disappear, unfortunately,” says Rulli.

Domoic acid may harm humans as well. It can cause a syndrome known as Amnesic Shellfish Poisoning, since it is primarily caused by eating shellfish that grew in algal bloom areas, and lead to severe memory impairment. Identifying the disease in sea lions can be the first sign of the problem, before the compound can harm humans. “When we see an algal bloom and note how it affects our patients, we inform public health services,” says Gill. “This way, they can investigate and close off a problematic fishing area, which otherwise can lead to people eating contaminated products.”

More generally, says Rulli, sea lions serve as a kind of sentinel species – through which we are informed about the health of the ocean and other species. “They serve as a window to greater potential environmental hazards, primarily to the health of humans – as sea lions spend most of their time near the shores and eat seafood very similar to what humans eat – fish, squid, and others. Thus, we can learn from the diseases that afflict the sea lions coming here, beyond the current and future patients, also about human health.”

Life in the warming waters

Perhaps the largest threat to life in the oceans, as well as to the entire world, is the climate crisis. Warming waters in the oceans promote algal blooms, also harming sea lions in other ways. When the temperature rises, fish search for cooler water farther from the shore, and sea lions pursue them further out to sea. This is a serious problem for mothers of young pups, which usually nurse for several days before going out to the sea to hunt for several days and then repeating the cycle. When their prey strays farther away, they remain for longer periods in the water, and the pups are left without food on the beach. “In their desperation, the malnourished pups dive into the ocean to search for food when they are not big enough,” says Rulli. “Often, they are stranded on different beaches, hungry and weak.”

“Every year, malnourishment is the primary reason for patients arriving at the center,” adds Rulli. “In the past, we had 600-800 malnourished patients annually. But in the past five years, there hasn’t been a year with less than 800. Overall, there are more cases in recent years.”

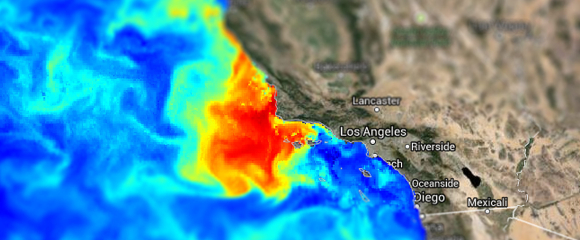

In 2015, a record number of malnutrition cases was noted, with around 1,800 pups brought to the center. Not surprisingly, in 2015 the waters around North America’s western beaches were especially warm. For reasons not clear yet, but are probably related to the abnormally hot summer in those areas in 2014, a region of warm water, up to 1,500 kilometers wide and 90 meters deep and nicknamed ‘the blob,’ formed along North America’s coast from Mexico to Alaska. The temperature in ‘the blob’ was 3-4 degrees Celsius higher than the typical temperature in that region. Last autumn, the temperatures in that area of the Pacific Ocean started rising again, and it is possible that we are on the way to another ‘blob.’

The climate crisis hits other marine mammals even harder. Due to rising sea levels, the breeding grounds of the northern elephant seal (Mirounga angustirostris), on the coasts of California and Mexico, are shrinking. “During a storm, the pups on the breeding beaches are at a higher risk of being washed away to sea and separated from their mothers,” Gill says. The Hawaiian monk seals (Neomonachus schauinslandi), an endangered species, live, as their name suggests, on the Hawaiian Islands, and some of the beaches serving as their breed and rest grounds have simply disappeared.

A result of the climate crisis. Concentrations of algal bloom (red) in California’s beaches in 2015. Source: NOAA.

The return of the elephant seal

The sea lion ‘invasion’ of Pier 39 had a mutually happy ending, but this is not necessarily the case every time wild animals and humans interact. Hunting regulations and conservation efforts have brought many species back from the brink of extinction, and resulted in their flourishing in recent decades. While an obviously welcome outcome, this also leads to increased friction between animals and humans, who, in the meantime, have settled into areas formerly inhabited by those wild animals, before their decline in numbers.

This was the case recently at the Point Reyes Federal Park in California, not far from San Francisco. Northern elephant seals are frequent park visitors, but over the past decades, park rangers have diligently partitioned beaches designated for the seals, to which humans cannot enter, from those designated for human use, from which rangers keep the seals away. But in early 2019, the U.S. federal services were shut down due to a political-budget crisis. National Parks were also shut down, and so, the rangers were not around when elephant seals moved into the bathers’ beach and claimed it for their own.

Upon their return, the rangers did not carry out any special measures to evict the invaders – not that they really had a way to do so. Paraphrasing a well-known joke – where does a three-and-a-half-ton elephant seal sit? Anywhere that pleases it.

The park’s beach served the elephant seals as a breeding ground and, at the end of the breeding season, they left. But these animals tend to return to the same beaches time and again, and no one knows what will happen next year. The problem at Point Reyes Federal Park is not very severe – in the worst case, park visitors will lose a beach, and gain a new place to observe elephant seals. But in other places, friction can be harsher.

“As the marine mammals’ population recuperates, they will increasingly come to places where humans, at least as far as modern settlements are concerned, are not used to encountering them,” says Rulli. “It is quite possible that they had previously inhabited these areas, but abandoned them because of hunting. Now they are returning.”

No one knows what will happen next year. Elephant seals at a beach in Point Reyes. Photography: Kenichi Ueda, Flickr

And in the meantime, in Israel

Israel does not have sea lions or elephant seals, and visiting marine mammals usually do not present any problem for the country’s beaches. But other wild animals live in close proximity to humans, and not always peacefully.

A famous example is Ruthi. She is a striped hyena (Hyaena hyaena) born on the southern slopes of the Modi’in hills, a (currently) undeveloped land inhabited also by gazelles, porcupines, foxes, and jackals. At one point, Ruthi realized that life is easier in the city itself – instead of looking for prey or carrion, she can find anything she wants in dumpsters or backyards, where people leave food for cats. She moved to the Reut neighborhood, and regularly patrols the streets. Not all the residents were thrilled about a wild, and potentially dangerous, animal prowling around their homes. Ruthi was caught, returned to the southern hills, but was shortly seen again on the streets of Modi’in. She is reported to have been captured again last August, and this time, the Nature and Parks Authority moved her farther away, to a secret location, which is probably far removed from humans or houses.

Additional wild animals that have been known to roam city streets are jackals. Several dozens of them live in the city of Tel Aviv, especially in the Yarkon Park and along the beach, roaming the northern neighborhoods at night. This troubles some of the residents, who fear that the nocturnal visitors will attack people or pets, and possibly infect them with rabies. However, jackal attacks are quite rare: These animals mostly fear humans and keep their distance. The correct thing to do, as far as humans are concerned, is to maintain the current state and not come closer to them. Zvi Galin, the municipal veterinarian, warned in an interview to Time Out in March 2019 not to feed the jackals. “Feeding compromises their natural characteristics, they are accustomed to finding their own food. This way they also lose their fear of humans and pets, and if another person approaches who does not want to feed them, they could get angry”, he said. Additionally, Galin explained that the main reason that the jackals enter the neighborhoods are to look for food in garbage cans – and it is possible to avoid a large part of these visits by proper maintenance of the garbage cans.

Jackals inflicted with rabies could become aggressive, and incidences of rabies have increased in recent years, due to sick jackals crossing from Syria to the Golan Heights. Despite this, it has been years since a rabies-infected animal was spotted in the center of the country, and in order to avoid the disease from spreading, local municipalities distribute bait containing vaccines for the jackals.

In many human-wild animal interactions, it is difficult to blame the animal for intruding into the cities – since these were built on lands in which they formerly roamed. There were always jackals in Tel Aviv, says Galin. “The new circumstances are that we are constructing more houses and taking over more open spaces, and are therefore seeing them more often”.

We invaded into their territory. A female golden jackal at the Yarkon Park in Tel Aviv. Photography: Wikipedia, Artemy Voikhansky.

The gazelles that were saved

The story of ‘Gazelle Valley’ in Jerusalem shows that in Israel, too, decisions can be made to conserve small tracts of nature and wild animals inside a city – but the journey was not an easy one. The valley, an area of around 250 dunams – or 60 acres – is located at the heart of the city, between neighborhoods and roads. For many decades, Israeli gazelles lived there, traversing the valley and the nearby open lands outside the city. But increased urban construction, primarily of the Begin highway, created a buffer that prevented the animals from moving out of the valley. A decrease in their habitat, with additional factors, such as an increase in waste that the gazelles consumed and harmed their health, roaming dogs that attacked them, and others, led to the drop in their population; they were quite close to disappearing altogether.

A success story. Gazelle Valley in Jerusalem. Photography: Wikipedia, Mathknight, Yuvalr.

Originally, Gazelle Valley was farmland, and it contained orange and plum trees. In the 1990s, the land’s designation was changed and a plan to construct housing complexes, offices, and commercial districts were drawn. The plans would have resulted in the destruction of land that can support wild animals, and to the destruction of the gazelle herd. A combined effort undertaken by social and environmental organizations succeeded in reversing the edict. In 2002, it was decided that the valley would remain a protected open space and later it was decided to turn it into a park. The park officially opened in 2015, one of the largest urban parks in Israel. The gazelle population recuperated: Last summer, 45 members were reported in the valley. Gazelle Valley is considered an impressive success in combining the city’s construction needs and nature conservation, and was featured in a film which represented Israel in a UN conference for sustainable development last July.

This story, like that of the sea lions in San Francisco, shows that the well-being of animals and that of humans is not necessarily contradictory. While it is not always possible, and sometimes there is no alternative but to distance animals from human settlements, under certain conditions, a solution that is beneficial for both sides – and also for visiting tourists – is within reach.