False news reports have been in existence since time immemorial, long before the term "fake news" emerged, but social networks turned them into a graver issue than ever before. Why is it so easy for us to believe them? How can we avoid falling for them?

In the autumn of 2016, a few days before the U.S. presidential elections, a user on Reddit posted a sensational report: the basement of a pizzeria in Washington D.C. serves as the headquarters of a pedophile ring, headed by Hillary Clinton, the Democratic presidential candidate, along with other senior members of the Democratic Party. The “proof”? A number of children’s photos from the Instagram account of James Alefantis, the restaurant’s owner, and the fact that Alefantis donated a large amount of money to the Democratic Party and his name was also mentioned in a leaked email, written on Clinton's behalf by her assistant.

Despite the weakness of the evidence, the story dispersed quickly among extreme right-wing circles in the U.S. In mid-November, after the elections, it was propagated when supporters of the President of Turkey, Erdoğan, in an attempt to direct the attention away from another affair he was suspected in, began spreading the story with the hashtag #pizzagate. Protesters began demonstrating in front of the restaurant, and in December, an armed man shot inside the restaurant and demanded to investigate what is going on in its basement. This pizzeria, incidentally, does not even have a basement.

What caused this story, and numerous others, to be accepted as a truth among a numerous readers? Why do some rumors appear plausible, while others seem to be obvious lies? When do we decide to believe a story we read and pass it on, and when do we just ignore it? In marking April Fools’ Day, we explore the psychology behind fake news.

Getting Away with a Lie

It is reasonable to assume that exaggerated stories, hoaxes, and rumors accompanied the story of our species from its very beginning. We know that printed exaggerations appeared very shortly after the invention of print, in the form of pamphlets sharing sensational reports with the public. In 1611, such pamphlets reported a Dutch woman who passed 14 years without eating or drinking. In 1654, a report in Catalonia stated that a monster with goat legs, the body of a human, seven arms, and seven heads was discovered.

In the 19th century, the emerging newspapers quickly joined in the party. One of the most famous hoaxes was posted by the New York Sun in 1835. It was a long piece about astronomer John Herschel (son of William Herschel) and what he discovered while observing the moon using a new, sophisticated telescope. The report claimed that the same telescope enabled him to see that the moon is inhabited by huge bat-people, who raise blue goats and build temples from sapphire stones.

Why did the pamphlets and newspapers publish obviously untrue stories? The motivation, of course, was to boost sales; the fake stories were very popular. Following the story about the moon people, for instance, the New York Sun's circulation surged from 8,000 copies per day to over 19,000. Until this very day, studies show that lies definitely spread farther than the truth.

In a 2018 study, researchers from the U.S. followed 126,000 stories posted on Twitter between 2006 and 2017, and categorized them as being either fake or real news, according to information that came from various fact-checking organizations, like Politifact or Snopes. They found that fake news dispersed faster and further than real news, especially political news. Buzzfeed reviewed Facebook posts in the three months preceding the 2016 U.S. elections, and found that the top 20 most popular fake reports received more than 8.7 million shares and comments. In contrast, the top 20 most popular reports from credible news websites only received 7.3 million shares and comments. What causes a lie to be more popular than the truth?

The answer does not lie in the type of people who share the fake reports, claim the researchers who studied the dispersion of tweets. Those who spread the real reports actually had more followers, followed more people, and were generally more active on Twitter. It was the posts themselves: the likelihood of fake reports to be retweeted was 70% higher compared to real ones. At least a partial explanation for this, according to the researchers, is the lies’ and fake reports’ novelty. Examining the fake reports, they found that these contain more new information, on average, than the real reports, and people responded to them with a sense of surprise. Novelties attract our attention and invoke our curiosity, and we also tend to share new information more – be it because we think it may be beneficial to others, or because it makes us appear as if we are in on some sort of secret. The story’s credibility, apparently, is secondary.

Previous Beliefs

Nevertheless, novelty is clearly not the whole story. We still need to explain why it is difficult for us to identify a made-up story as such, when others quickly dismiss it as false. Many researchers believe the reason for this are previous perceptions we hold, which tint the reports we hear or read.

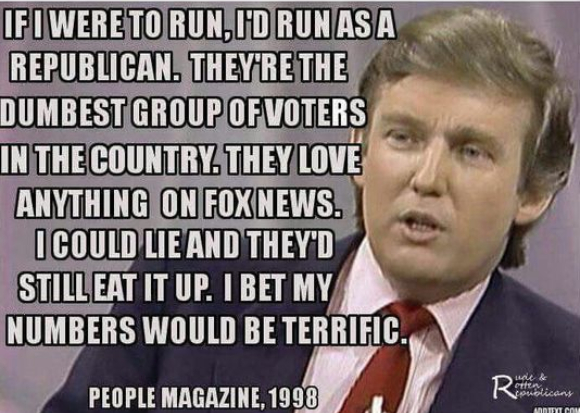

Confirmation bias is our tendency to pay attention, remember, and also believe stories and cases that fit what we already think, while details that do not fit our beliefs are quickly forgotten. We also judge stories or posts on social networks according to how well they fit our previous beliefs. In 2016, a meme was posted on Facebook supposedly quoting Donald Trump in a 1998 interview, saying: “If I were to run [for president], I’d run as a Republican. They’re the dumbest group of voters in the country. They believe anything on Fox News. I could lie and they’d still eat it up. I bet my numbers would be terrific.”

The “quote” is completely made up; Trump never said this. However, many people believed the meme, which was shared and spread throughout the internet. Psychologist David Braucher was one of those who shared the meme, and on his blog post on the website Psychology Now he explained what made him believe it: “I always believed that Donald Trump was in the Presidential race for his own gain. Also, he didn’t seem to be ideologically wedded to either party. He had been a campaign contributor to both over the years. So, when I saw this meme I didn’t even question that it could not be real. I overlooked the fact that the photograph depicts him 10 years younger than the date stated and that publishing such a statement would be obviously counterproductive for a Presidential bid. It simply confirmed what I already thought, and I bought it.”

A similar thing probably occurred in the minds of people holding extreme right-wing opinions when they read the Pizzagate report. They already believed the leader of the Democratic Party was a questionable person who could not be trusted. The pedophile ring story fit these perceptions, and they shared it without bothering to check if it is real.

It may sound typical to Trump, but he never said it. The meme that was dispersed before the U.S. presidential elections

Knowledge Versus Tribalism

Another cognitive bias that affects the way we read posts and news reports is our tribal tendency – dividing people into “us” and “them”. Information we receive from people that belong to our group – friends, family, or those with shared interests, religious beliefs, or political views – will appear more reliable than information coming from outside of our group. In addition, we choose what information to take seriously and what to ignore, based on its compatibility with the values and belief system of our group.

In the past, the common assumption was that the more we know, and the better we are at logical and scientific thinking, the harder it would be to make us “buy” into something that is not true. However, research from recent years shows that this is not exactly the case, and that scientific thinking may even lead us to sticking to tribal perceptions.

In 2012, a study examined the opinions of responders regarding global warming, and asked them to estimate “How much risk it poses to human health, safety, or prosperity.” In parallel, the researchers also examined responders’ scientific literacy and proficiency in understanding quantitative information. These tests included questions such as “Antibiotics kill viruses as well as bacteria [true/false],” and “A bat and a ball cost 1.00 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?”

Global warming, or climate change, is a widely accepted scientific theory, and so is the risk it poses to the human race. Outside of the scientific world, though, it is a different story. In the study, there were responders who assessed the risk as being high and those who claimed it is low. In contrast to what might be expected, the responders who scored high on the scientific literacy test were no closer to the scientific consensus regarding global warming. Their responses were polarized and matched the opinions of the groups they belong to.

“Ordinary members of the public credit or dismiss scientific information on disputed issues based on whether the information strengthens or weakens their ties to others who share their values,” said Dan Kahan, who led the study. “…individuals with higher science comprehension are even better at fitting the evidence to their group commitments.”

This phenomenon is prevalent not only with regards to climate change, but in any conflictual issue: using nuclear power plants, fracking (a method for extracting oil and gas from the ground), limiting weapon sales, etc. Kahan calls it “identity-protective cognition”: using our abilities to understand and interpret scientific evidence not to unravel the truth, but to reinforce the bonds between our perceptions and the views of our group, and thus reinforce our identity, the way we define ourselves.

The “stranger” and further from the consensus the perceptions of people, the more they tend to stick together and dismiss any information coming from outside of their group. This can be observed, for example, among those who believe the Earth is flat and that any evidence of its round shape is part of a conspiracy. “We all have a tendency to want to connect with people revolving things that make us unique,” said psychiatrist Joe Pierre in the documentary depicting the phenomenon, Behind the Curve. “And we know that people feel very threatened when they feel that identity is being taken away from them.”

Is climate change dangerous? Depends on the group you belong to. A picture from the 2014 march in New York | Photograph: Jim West, SPL

The Answer: Curiosity?

What can get us out of this situation, where we only pay attention, listen, and believe information that comes from our group and fits our views? Kahan has an answer: curiosity. He and his colleagues have developed a test that examines responders’ scientific curiosity – to what extent do they search and consume scientific information. They showed that people who scored high in scientific curiosity had a lower tendency to adhere to previous perceptions and reassess new information according to the values of their group.

Kahan wrote in an article in Scientific American, “Afforded a choice, low-curiosity individuals opt for familiar evidence consistent with what they already believe; high-curiosity citizens, in contrast, prefer to explore novel findings, even if that information implies that their group’s position is wrong. Consuming a richer diet of information, high-curiosity citizens predictably form less one-sided and hence less polarized views.”

Kahan suggests focusing on developing scientific curiosity among the general public, since without it, he says, attempts to communicate important scientific information, such as the dangers of climate change, are bound to fail. “Merely imparting information is unlikely to be effective – and could even backfire – in a society that has failed to inculcate curiosity in its citizens and that doesn’t engage curiosity when communicating policy-relevant science,” he writes.

Mental Laziness

Not everyone agrees with Kahan. The main problem, claims MIT’s David Rand, is not necessarily cognitive bias and sticking to tribal values. “It's just mental laziness,” he said in an interview to Wired. Rand and his colleagues found that people with high analytical and information processing abilities, such as those reflected by the answers to questions like the one about the cost of the ball and the bat, were better at identifying false reports, even if they were in accordance with their views.

It is not that we are somehow biased, claims Rand; we just do not think enough about what we read or hear. This can be seen as an encouraging message: it is extremely difficult to change people’s political views, and even more so, the deep beliefs they perceive as part of their identity. But it may be easier to provide them with analytical tools and encourage them to use them more often. Nonetheless, this is also probably not so simple.

“I think social media makes it particularly hard, because a lot of the features of social media are designed to encourage non-rational thinking,” says Rand. Our news feed on Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram leads us to skim through the posts, without looking into them in-depth. A recently published study showed that people relax as they are browsing through Facebook – we go into social media for entertainment and relaxation, not to read content that will challenge us, force us to think or encourage us to take action.

Social Media and Echo Chambers

Even if researchers are divided on why people believe fake news and how this can be overcome, it seems that they all single out social media as a harmful factor. Made-up stories have always existed and were dispersed through the available means. But it is possible, according to some researchers, that there is still something unique about the internet and social media in particular, which enables any person to share their opinions easily and quickly with many others.

Social media also gives us the illusion that we are connected to a variety of people, opinions, and viewpoints, but for most of us, this is not really the case: the posts presented to us come from a small and specific sector of opinions. Each person can find their group online – this could be wonderful, but can also isolate us in an environment that echoes the views we already hold.

“Online, we tend to associate with the people who have the same political leanings as we do,” writes Braucher. “When our ‘friends’ send us fake-news articles that conform to what we already believe, reflecting our confirmation bias, we are likely to buy the ‘information’ wholesale. Moreover, audience optimization in sites like Facebook ensures that our feed includes the news we tend to read and these news further confirm our biases.”

The groups we create for ourselves on social media do not only lead us to being exposed mostly to reports that match our perceptions so that we believe them – having come from our “friends,” after all – they also affect our way of thinking. When we are rarely exposed to information that opposes our values, our tolerance towards such information diminishes, and along with it, our willingness to test it and challenge previous views. The result is a society in which, despite numerous opinions and views, each political or ideological group communicates mostly within itself and has a different perception of what counts as rational, legitimate, or even factual.

“We no longer need to be holed up in a log cabin or socially isolated,” writes Braucher. “We can live in the biggest city in the country, and as long as we keep our faces buried in our smart phones, we will feel connected to the group we belong to and read the information we want to believe. And we will be sitting ducks for anyone who wants to feed us fake news!”

Bots and External Influences

Who feeds us fake news? Most of the people who spread fake reports do so, most likely, without malicious intentions, truly believing that the information they are spreading is true and important. However, there are organizations that use fake news as a weapon, in order to influence the opinions of readers, change public debate, or simply create confusion and chaos.

Often, these organizations do this by using “bots” – computer programs that create and share posts, while pretending to be human users. These programs are very prevalent: 9-15% of active Twitter accounts are bots, and Facebook estimates the number of bots on its network at 60 million. Bots can substantially increase the distribution of fake reports, and often aim to create an atmosphere supporting a candidate or an opinion that does not have such a wide support in reality, or one strongly opposing certain people or other views.

Websites such as Facebook and Twitter try to fight these programs, but this is a technological “arms race,” in which any algorithm developed to detect and block bots is countered by more sophisticated bots that can evade the algorithm.

Before the 2016 U.S. presidential elections, for instance, Russia used thousands of bots on Twitter pretending to be U.S. citizens, and tweeted 1.4 million times within a two-and-a-half-month period. Hundreds of fake Facebook accounts spread false reports and invited to join groups of Russian users pretending to be Americans. It is very difficult to know what the effect of it was, but Kathleen Jamieson, who wrote a book about it, said in an interview to the New Yorker that the scenario in which Russia determined the results of the elections is not only possible, but also very likely.

Do these sorts of things also happen in Israel? It seems so. Noam Rotem and Yuval Adam started the Big Bots Project, which aims to expose political bot networks, and have already publicly exposed such a network, which was most likely operated by a foreign source. The network’s accounts, pretending to be Jewish Israeli residents, posted supportive tweets about Prime Minister Netanyahu but opposing his wife, phrased in a way that raised the suspicion that it was not written by Hebrew speakers. Among others, they wished the readers “Happy Yom Kippur” and posted a photo of the Kotel under the title “The Holy Western Wall.”

So What Can Be Done?

Of course, the core issue is not a computer program, but human psychology – our willingness to believe fake reports and pass them on. So how can the websites that disperse them, especially social networks, diminish their effect?

Websites such as Facebook and Twitter have rules and regulations that enable them to remove certain posts, but these focus more on preventing the spread of hate and incitement and less on misinformation in general. Nevertheless, they are not very effective, especially in non-English speaking countries. In Myanmar, for instance, many residents have Facebook accounts and certain groups use them to spread lies and incite hatred and fear of the country’s Rohingya minority. Facebook has difficulties in dealing with these posts, since the company employs only four Burmese speakers. And this is an improvement over the single Burmese speaker employed prior to 2014.

David Rand suggested that social networks could be able to detect unreliable sources efficiently by activating their users. In a recently published study, Rand and his colleagues asked people to rate the credibility of different sources, including mainstream media outlets, hyper-partisan websites, and websites that produce blatantly false content. The rating created by the participants was compatible with the rating produced by professional fact-checkers who surveyed these websites in depth. An algorithm based on user feedback about the credibility of the source might be a “promising approach for fighting the spread of misinformation on social media,” according to the researchers.

Researchers who published a paper about the science of fake news also suggest that social networks should display a credibility rating for a report’s source. Another suggestion is to change the algorithm that creates the situation in which news presented to a specific user are similar to news that user has read in the past, a pivotal component in forming the aforementioned “echo chambers” in which a single viewpoint is presented.

One field in which Facebook has recently decided to take on fake-news vectors is the anti-vaccination movement (aka anti-vaxxers). Anti-vaxxer groups are very common on Facebook and on other online sources, and the “information” they spread has already led numerous parents to refrain from immunizing their children – enabling the outbreak of diseases like measles. The real-life damage caused by anti-vaxxers has led Facebook to declare a battle on the phenomenon, stating that they will take the following measures: “We will reduce the ranking of groups and pages that spread misinformation about vaccinations in News Feed and Search; When we find ads that include misinformation about vaccinations, we will reject them; We won’t show or recommend content that contains misinformation about vaccinations on Instagram Explore or hashtag pages,” and “We are exploring ways to share educational information about vaccines when people come across misinformation on this topic.” Will these steps, which do not include removing posts or shutting down the anti-vaxxer groups, really be effective? Time will tell.

Don't Be Lazy

Even if Facebook, Twitter, and other social networks would embrace all of the recommendations and even fully apply them, it is still up to us, the users, eventually facing a report, to decide if it is real or not. In 2016, the Huffington Post published a guide on How to Recognize a Fake News Story which can assist us in this. It recommends finding out details, such as the source of the report, its author, and also when it was first published – the fake report on how Mars would appear as large as the moon, for instance, was published year after year, with a different date.

Another good piece of advice is checking whether the report was published in additional places. The death of a famous actor, for instance, would not be reported solely on one news website: so before sharing the report, it is a good idea to go to other websites and see if it appears there as well. There are also websites that specialize in fact-checking, such as Snopes and FactCheck.org.

The most important piece of advice is to recognize our cognitive biases and try to prevent them from making us fall for misinformation. To thoroughly check not only reports that are very hard for us to believe, but most importantly, those that we can easily believe, that correspond to everything we already think. Every time we read something and think “oh that's obvious” should be taken as a warning sign to use a healthy dose of curiosity, particularly for such cases. This is no easy feat: it means working against our own biases, as well as our inherent mental laziness. After all, we go on Facebook to relax, not work. But if we really want to become resistant to fake news, the only way, as Rand put it, is “don't be lazy.”