Marking 31 years since the death of Primo Levi, an Auschwitz survivor who became one of the most prominent and important Holocaust writers

”Primo Levi died in Auschwitz, only 40 years later,” said Holocaust survivor and writer Elie Wiesel, following the mysterious death of the Italian writer and chemist, and one of the most important and acclaimed authors writing about the Holocaust. To this day, it is not clear whether Levi's death 31 years ago was an accident or a suicide. It is, however, very clear that Levi may have survived Auschwitz – in part, thanks to his scientific training – but never really broke free from it.

A cloud of possibilities

Primo Michele Levi was born on July 31, 1919 in Turin, the eldest child of a family whose ancestors had first settled in Northern Italy as early as the 16th century, following the Alhambra Decree. His father, Cesare, an electrical engineer employed by a Hungarian company, travelled to Hungary frequently. Primo’s mother, Ester (of the Luzzati family) was, like her husband, an avid reader and a music lover. A skinny, short, and sickly child, Levi was usually the only Jew in his class. He was an outstanding student throughout his school years, regularly at the top of his class, and began to take an interest in chemistry during high school.

In his famous book The Periodic Table, he described his aspirations to be a chemist as an adolescent: “For me chemistry represented an indefinite cloud of future potentialities which enveloped my life to come in black volutes torn by fiery flashes, like those which had hidden Mount Sinai. Like Moses, from that cloud I expected my law, the principle of order in me, around me, and in the world.”

Indeed, in 1937, Levi began studying chemistry at the University of Turin. A year later, Mussolini's Fascist regime passed the racial laws that prohibited Jews from studying at institutes of higher education. Since he began his studies before the law came into effect and because one of his professors supported him, he was permitted to submit his final project and graduate. In 1941, Levi completed his degree in chemistry with excellence, but his diploma bore an “of Jewish race” stamp, effectively depriving him of any chances of finding employment as a chemist.

After several months of unemployment, Levi found a job using a fake identity at a nickel mine – a valuable metal at the time of the war – and one of the ores in the region. After months of work, he developed a method for producing large amounts of nickel, but it was abandoned because the means to implement it were lacking. This was one way Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany did not acquire their nickel.

In 1942, Levi concluded his work at the mine and found a job at the Milan laboratory of a Swiss pharmaceutical company, attempting to find an oral medication for diabetes. He produced plant extracts and tried them on diabetic rabbits, but his work was discontinued once the factory was bombed and the rabbits ran away.

In 1943, Levi resigned from the factory and joined the partisans in Northern Italy. Following Mussolini’s overthrow and imprisonment, Hitler sent his troops to release his ally from prison and placed him as the leader of the puppet regime that ruled Northern Italy, while German troops take over the region.

Expectations that chemistry would fix the world. Primo Levi, aged 8, with his family in 1927 | Source: Wikipedia

Hopes of telling the story

Lacking military experience and training, Levi and his friends ultimately did not have the opportunity to fight the Germans or the Fascist Italians. An informant tipped off the Fascist militia in December 1943 and they were arrested and held in custody. When his imprisoners discovered that Levi was Jewish, they transferred him in January 1944 to Fossoli camp, next to the city of Modena. Fossoli began as a camp for prisoners of war and political prisoners and gradually became a Jewish concentration camp. On February 21, the 650 Jews in the camp, including Levi, were loaded on crowded freight trains.

The five-day journey included numerous stops, but the prisoners were never given an opportunity to get off the train car. Levi was crammed in the car with 45 others, horrendously crowded and tortured by the freezing cold, thirst, and hunger. At the end of these five days, the train arrived in Auschwitz. Following a quick screen of those capable of work, Levi's arm was tattooed with the number 174517.

Levi was sent to the Auschwitz III camp, also known as Monowitz-Buna, named for the Buna synthetic rubber factory and the nearby town of Monowice (pronounced Monowitz in German). The camp’s prisoners were engaged in physical labor, unloading coal from trains, hauling heavy pipes, mining or digging, while they coped with hunger, thirst, freezing winter temperatures, physical abuse, torture, and humiliation.

To survive in the camp, Levi realized he had to be knowledgeable about his environment. During his chemistry studies, he tried to read textbooks in German, so he was familiar with the language. He paid other prisoners bread for German lessons, as well as used the help of an Italian civilian worker, Lorenzo Perrone, who shared leftovers from his food with him, showed him around the camp, as well as assisting him in other ways. Perrone was later named Righteous Among the Nations.

In November 1944, after nine months in the camp, Levi was promoted to the position of an “expert” and stationed for work at one of the rubber factory’s labs. The strenuous physical labor in the Polish winter would now be replaced with much easier work in the heated lab. He also managed to steal soap and petrol from the labs to sell to other prisoners. During this time, Levi began writing about his experiences in the camp, with the hope of living to tell his story.

On January 11, 1945, when the sounds of the Russian Army's bombings could be heard loud and clear, Levi became ill with scarlet fever and was admitted to the camp's hospital, Ka-Be. A week later, the Germans abandoned the camp, forcing tens of thousands of its prisoners onto a “death march.” Their hasty departure led the Nazis to leave the hospitalized prisoners behind; for them, it would mean nine more days of surviving without food or heating until the Soviet forces would finally arrive at the camp on January 27, the official liberation day.

Slave labor in the freezing cold, hunger and torture. Labor prisoners at Monowitz-Buna camp | Source: the German Federal Archive, Wikipedia

A long journey

After the camp was liberated, Levi’s journey back home was no simple matter. He was first transferred to a camp for former prisoners in Katowice, Poland, working for a few weeks as a pharmacist's assistant. From there, he found himself in the Soviet Union, first in Ukraine, then in a displaced persons’ camp in Belarus, where he also worked for several weeks as a doctor's assistant, until the camp was closed. In post-war Europe, the journey back to Italy took 35 days by train, through Hungary, Slovakia, Austria, and Germany. Finally, in October 1945, Levi returned to his family home in Turin, nine months after the liberation of Auschwitz and 20 months after he was sent there. Out of some 8,000 Jews sent to the extermination camps since the regime change in Italy in 1943, less than 700 survived.

Bruised and malnourished, Levi was hardly recognizable to his mother and sister upon his return. In early 1946, he began working as a production chemist at a Du Pont Company paint factory near Milan. In the end of 1947, he left the factory and established a chemical consultancy together with an old friend. During the same time, he also met Lucia Morpurgo, and the two fell in love and married in September 1947. A number of months later, when Lucia was pregnant with their eldest daughter, Levi decided to give up the uncertainty of self-employment and took a job at the SIVA paint factory in Turin. He was promoted to the position of factory technical director and later, to general director. In 1974, he resigned from the director's position, and, until his final retirement in 1977, remained at the factory as a consultant.

Rigorous laboratory conditions

Immediately after his liberation from Auschwitz, Levi began documenting his experiences at the camp. He first wrote – as the Russian authorities requested from him – a report on life inside the camp, which was published in full only years later. Parts of the report were combined with more personal memories, and processed into the book If This Is a Man, which he wrote in 1947. Levi sent his scripture to the famous Einaudi publishing house in Turin, but was rejected, both because he was an unknown writer and because they felt the wounds of the war were still too fresh.

Eventually, Levi found a small publishing house, Antonicelli, which was willing to print 2,000 copies of the book. It did not sell very well, and even this limited edition was not sold out, despite a positive review by the famous writer, Italo Calvino.

It would be over a decade later that Einaudi decided to publish a newly edited version of the book. This time it was very successful, especially after its translation into English, and later also into German. In the book, Levi chillingly describes life at the death camp. “Thousands of individuals, differing in age, condition, origin, language, culture and customs, are enclosed within barbed wire: there they live a regular, controlled life which is identical for all and inadequate to all needs, and which is more rigorous than any experimenter could have set up to establish what is essential and what adventitious to the conduct of the human animal in the struggle for life.” (Translated from Italian by Stuart Woolf).

A chilling description of life at the death camp. A stamp issued in Italy in memory of Levi | Source: Shutterstock

I write because I am a chemist

In 1961, Levi began writing his second book The Truce, describing his long and difficult journey from the liberated Auschwitz back home. The book was published in 1963 and was the first to win the Italian Campiello literary award. During this time, Levi began suffering from episodes of depression, which most likely recurred throughout his whole life.

His literary success made Levi famous in Italy. He regularly wrote for the newspaper La Stampa, gave interviews in Italy and elsewhere, and took part in creating adaptations of his books into radio shows and plays.

While still working at the factory, Levi wrote many other books, including short stories, novels, and poetry. Most of them were based on his personal memories, both from the Holocaust and from his career as a chemist. Among his most noted books are The Drowned and the Saved, Moments of Reprieve, and The Monkey Wrench, which also received an important literary award in Italy. His best-known book is The Periodic Table, an autobiography in which each chapter is named after a different chemical element that is linked to its contents, directly or metaphorically. In the opening chapter, Argon, Levi surveys his family history and compares his ancestors, who were “inert in their inner spirits,” to the noble gases.

His life, his work as a chemist, and his writing were tightly interconnected. “I write because I am a chemist. My trade has provided my raw material, the nucleus to which things join,” Levi said in an interview. “Chemistry is a struggle with matter; a masterpiece of rationality, an existential parable ... Chemistry teaches vigilance combined with reason. When reason succumbs, Nazism and fascism prevail"

Surprisingly enough, in Israel Levi's books were not appropriately recognized. During his only visit to Israel, in 1968, Levi tried to interest publishing groups in translating If This Is a Man, to no avail. Yitzhak Garty, who met Levi during his visit and would later translate the book into Hebrew, told Ha'aretz that “Levi told me that he went to publishing groups in Israel and suggested that they translate If This Is a Man. They said, Holocaust? We have too many of those. Nobody will buy it.”

Only in 1979 was The Truce published in Hebrew. If This Is a Man and The Periodic Table were only published in Hebrew in 1987, after Levi's death.

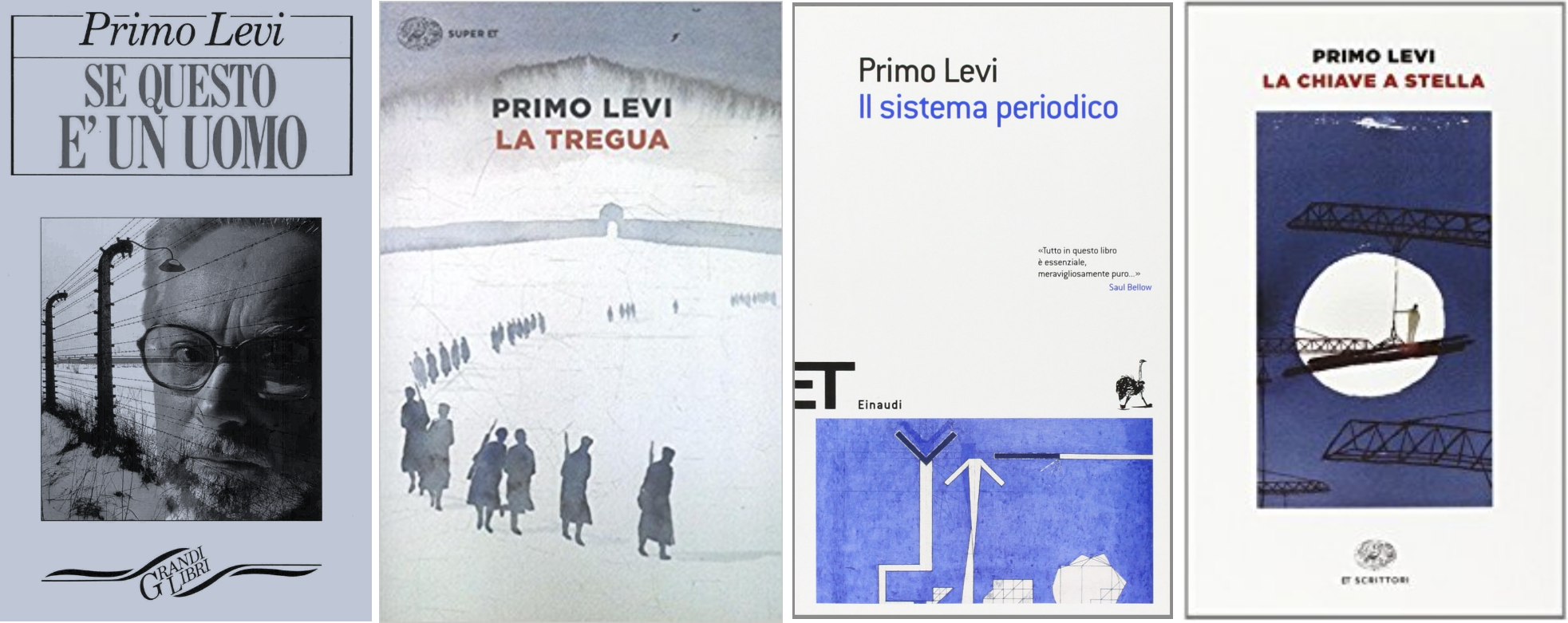

Levi's most prominent books (in Italian). From left: If This Is a Man, The Truce, The Periodic Table, and The Monkey Wrench

The number on the tombstone

On April 11, 1987 the concierge found Levi's body lying on the entryway staircase to the building on Umberto Street in Turin, where Levi resided on its third floor all of his life. He was killed by the fall. To his request, his prisoner number from Auschwitz –174517 – was engraved on his tombstone.

The coroner ruled Levi's death a suicide, and three of his biographers – Carole Angier, Ian Thomson, and Myriam Anissimov agreed with this claim. According to them, Levi succumbed to his depression, but in contrast to Elie Wiesel, they did not tie it directly to his experiences during the Holocaust. Both Thomson and Angier believe that Levi would have ended his life earlier, were it not for the sense of purpose that writing and talking about Auschwitz gave him.

Nevertheless, a number of his friends believe his death resulted from an accident. They mention that he did not leave a suicide note or any other hint of his intentions, and documents from his last days demonstrate that he had plans for the future. In addition, they say that he complained about being light-headed in the days preceding his death. His close friend, Nobel Prize laureate Rita Levi-Montalcini, said that as a chemist, Levi could have chosen a much easier suicide method and not risk a fall that could have left him paralyzed.

Levi's heritage endures after his death. His books are important documents in the study and teaching of the Holocaust. In 2006, the Royal Institution in London chose The Periodic Table as the best science book ever written. And The Truce was adapted in 1997 into a film of the same title, starring John Turturro.

“With the moral stamina and intellectual poise of a 20th-century titan, this slightly built, dutiful, unassuming chemist set out systematically to remember the German hell on earth, steadfastly to think it through, and then to render it comprehensible in lucid, unpretentious prose,” eulogized the American writer Philip Roth in The New York Times. “He was profoundly in touch with the minutest workings of the most endearing human events and with the most contemptible.”

Translated by Elee Shimshoni