In 2017, there are still fewer girls than boys majoring in sciences. Why does this happen, and what can we do promote a more balanced picture?

A year ago, the Henrietta Szold Institute for Research in the Behavioral Sciences conducted a study on the untapped potential for excellence among girls in mathematics and sciences. The study was based on data collected on high school graduates from 2010 to 2014, who took at least one matriculation exam. The picture arising from the data was quite problematic – there are significant differences between the percentage of girls compared to boys who took the high-level mathematics, physics, and computer science exams: in mathematics, 12% of the male students took the 5-point level exam, compared with only 9% of the female students; 13% of the male students majored in physics, compared with only 6% of the female students; and 10% of the male students majored in computer science, compared with only 4% of the female students.

In comparison to these fields, the percentage of girls who chose to major in biology was actually higher than that of boys – 20% vs. 12%, and so is the case in chemistry – 10% vs. 7%.

Why is it important to encourage girls to major in sciences?

The majors students choose during high school have a strong impact on their choices later in life. In addition, certain majors, such as 5-point-level mathematics, open doors for higher education, and are a prerequisite in certain academic departments. Also, gender diversity, in every field, but especially in academia, encourages creativity, originality and innovation, as well as an environment that is easily adaptable to the ever-changing world around us. Moreover, school is perceived as a place in which we should all have equal rights, and where success is based only on merit and effort. The abilities and tools that students acquire throughout high school and in higher education translate into income and social status – therefore, it is important that female students have those same opportunities.

The researchers tried to understand what are the reasons for the gender differences they found in Israel, and what could be done in order to ensure that girls fulfill their full potential in scientific subjects. They analyzed and processed data from the Ministry of Education regarding major choices and grades between 2010-2014 in mathematics, physics, chemistry, biology, and computer science. In addition, they conducted interviews with female students, parents, teachers, experts in gender studies, and experts from the Ministry of Education.

Untapped mathematical potential

To answer the question of potential in mathematics, the researchers compared female graduates of 5-point-level mathematics to those of 4 or 3-point levels. They found the graduates of the 5-point level differ from the others in that their parents tend to have academic degrees, and that they come from schools with students from high socioeconomic backgrounds. This means that choosing 5-point-level mathematics is related also to the familial situation and socioeconomic status, and it is reasonable to assume that there are female students with untapped potential as a result of environmental factors and not scientific capabilities.

Where does the preference of biology and chemistry come from?

The interviews conducted by the researchers yielded some information regarding the students' preferences: female students chose biology and chemistry because they perceived these majors as more useful for their futures in professions such as medicine and pharmacology. Furthermore, the girls expressed their fear of failure and a will to excel, and therefore were intimidated by subjects like physics, in which it is generally more difficult to excel. Another factor that deterred the students was their distaste with the competitive environment that characterizes scientific majors. When asked why they did not choose to study mathematics at a 5-point level, the most common reply was that they were not good enough. When closely examined, it was apparent that their opinion was not based on previous achievements or grades, but on negative environment-based stereotypes or low self-esteem.

The study also showed that the fellow classmates were the most significant factor in the female students' choices, causing boys to choose physics and high-level mathematics and girls to avoid them. Many female students feel uncomfortable and inferior when they are a minority in a science class, and are afraid to fail in comparison to other students. In certain cases, girls described instances of boys bullying girls, explicitly saying that girls should not be learning complex scientific subjects since they “are not for girls.” This can also progress into exclusion of female students from class activities and initiatives, such as Whatsapp groups in which students discuss the study material and help each other. In addition, the female students indicated that their different approach to studying led to tensions between them and the male students – while they are interested in deepening their understanding of the material, the male students are more interested in progressing to the next topic, without in-depth understanding.

Another reason that led less female students to choose physics and 5-point-level mathematics was the lack of a role model – in these subjects male teachers were the majority, in comparison to a more female faculty in biology and chemistry. This situation reinforced their perception that physics and mathematics are more “masculine” fields and not suitable for them.

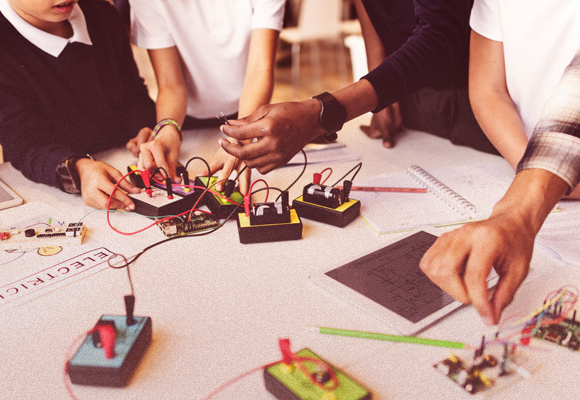

Girls sometimes hear that “physics and mathematics are not for girls.” A physics class| Photograph: Shutterstock

What happens when a female student excels and when a male student fails?

For years, researchers have attempted to understand the source of these gender differences in representation and achievements. One hypothesis states that the differences in achievements and career choices stem from gender differences in self-perception. For instance, researchers have shown that women, compared to men, perceive themselves as less mathematically inclined, and have lower expectations with regards to their grades, even before taking the exam, despite very small differences in actual exam grades. Other studies have indicated substantial differences between the ways in which male and female students interpret success and failure in exams in general: when female students succeed, they attribute their success to external factors – for instance, “the exam was easy” or, “I was lucky.” In contrast, when they fail – they blame themselves and question their abilities. Male students display an opposite tendency: successes are attributed to themselves – “I am smart and understand the material,” and failures are blamed on the environment – “the exam was difficult.”

And how does all of this pan out?

These different approaches towards success and failure are called attributions. An internal attribution is when we attribute something to ourselves (e.g., personal ability, effort), and external attribution is when we attribute something to the environment (e.g., luck, external assistance, the difficulty of the task at hand). Research shows that emotions such as pride and shame stem from internal, rather than external, attributions – for instance, we will not feel ashamed of our failure if we think it happened because the exam was very difficult. In contrast, if we attribute our failure to our lack of understanding of the study material, it reflects negatively on us. And what does this mean with regards to the female students? When they succeed, they do not feel proud or self-confident, since they do not attribute the success to themselves. Whereas when they fail, they feel ashamed, because they usually attribute failure to themselves. These perceptions shape their self-esteem and sense of competence, a decisive factor in deciding about a major. Later on, the different attributions made by male and female students can impact their tendency to study mathematics: when female students attribute failure internally and success to externally factors, they assess their ability as low, so they opt to avoid mathematics-involving subjects. By comparison, male students attribute their success internally and their failures to the environment, which leads them to assess their ability as high – and pursue the study of mathematics. It should be noted that the studies show that the tendency to either avert or select mathematics does not stem from a difference in achievements between female and male students, but mainly from their self-expectations and internal attributions.

What can be done?

To address the challenges that girls face when choosing scientific majors, the researchers recommend, first and foremost, to change the common perceptions among school faculty, parents, and students – both female and male. To facilitate girls’ choosing mathematical and scientific studies, it is important to explain the situation and the possible contributing factors, and encourage a discussion about gender stereotypes and the incorrect perceptions of these subjects as “masculine.” Such fields can also be made more accessible to female students by exposing them to the field early on, for example, by organizing meetings with inspirational role models such as female high-school students majoring in sciences and women who work in these fields in education, academia, and industry. Since, as mentioned above, these perceptions do not begin with the students themselves, but have probably been passed on from generations before them, it is important to work with school principals, teachers, and counselors and explore their stereotypical perceptions of scientific subjects and how they influence their attitudes towards their female students.

Translated by Elee Shimshoni