What happens if a time traveler kills his or her grandfather? What is a time loop? How do you stop a time machine from just appearing somewhere in space, millions of kilometers from home? And is there such a thing as free will?

Congratulations! You have a time machine! You can pop over to see the dinosaurs, be in London for the Beatles’ rooftop concert, hear Jesus deliver his Sermon on the Mount, save the books of the Library of Alexandria, or kill Hitler. Past and future are in your hands. All you have to do is step inside and press the red button.

Wait! Don’t do it!

Seriously, if you value your lives, if you want to protect the fabric of reality – run for the hills! Physics and logical paradoxes will be your undoing. From the grandfather paradox to laws of classic mechanics, we have prepared a comprehensive guide to the hazards of time travel. Beware the dangers that lie ahead.

A comprehensive guide to time-travel hazards. The machine from H. G. Wells’ “The Time Machine”. Credit: Shutterstock.

The Grandfather Paradox

Want to change reality? First think carefully about your grandparents’ contribution to your lives.

The grandfather paradox basically describes the following situation: For some reason or another, you have decided to go back in time and kill your grandfather in his youth. Yeah, sure, of course you love him – but this is a scientific experiment; you don’t have a choice. So your grandmother will never give birth to your parent – and therefore you will never be born, which means that you cannot kill your grandfather. Oh boy! This is quite a contradiction!

The extended version of the paradox touches upon practically every single change that our hypothetical time traveler will make in the past. In a chaotic reality, there is no telling what the consequences of each step will be on the reality you came from. Just as a butterfly flapping its wings in the Amazon could cause a tornado in Texas, there is no way of predicting what one wrong move on your part might do to all of history, let alone a drastic move like killing someone.

There is a possible solution to this paradox – but it cancels out free will: Our time traveler can only do what has already been done. So don’t worry – everything you did in the past has already happened, so it’s impossible for you to kill grandpa, or create any sort of a contradiction in any other way. Another solution is that the time traveler's actions led to a splitting of the universe into two universes – one in which the time traveler was born, and the other in which he murdered his grandfather and was not born.

Information passage from the future to the past causes a similar paradox. Let’s say someone from the future who has my best interests in mind tries to warn me that a grand piano is about to fall on my head in the street, or that I have a type of cancer that is curable if it’s discovered early enough. Because of this warning, I could take steps to prevent the event – but then, there is no reason to send back the information from the future that saves my life. Another contradiction!

Marty finds himself in hot water with the grandfather paradox, from ‘Back to the Future’ 1985

Let’s now assume the information is different: A richer future me builds a time machine to let the late-90s me know that I should buy stock of a small company called “Google”, so that I can make a fortune. If I have free will, that means I can refuse. But future me knows I already did it. Do I have a choice but to do what I ask of myself?

The Time Loop

In the book All You Zombies by science fiction writer Robert A. Heinlein the Hero is sent back in time in order to impregnate a young woman who is later revealed to be him, following a sex change operation. The offspring of this coupling is the young man himself, who will meet himself at a younger age and take him back to the past to impregnate you know whom.

Confused? This is just one extreme example of a time loop – a situation where a past event is the cause of an event at another time and also the result of it. A simpler example could be a time traveler giving the young William Shakespeare a copy of the complete works of Shakespeare so that he can copy them. If that happens, then who is the genius author of Macbeth?

This phenomenon is also known as the Bootstrap Paradox, based on another story by Heinlein, who likened it to a person trying to pull himself up by his bootstraps (a phrase which, in turn, comes from the classic book The Surprising Adventures of Baron Munchausen). The word ‘paradox’ here is a bit misleading, since there is no contradiction in the loop – it exists in a sequence of events and feeds itself. The only contradiction is in the order of things that we are acquainted with, where cause leads to effect and nothing further, and there is meaning to the question “how did it all begin?”

Terminator 2 (1991). The shapeshifting android (Arnold Schwarzenegger) destroys himself in order to break the time loop in which his mere presence in the present enabled his production in the future

Time travelers – where have all they gone?

In 1950, over lunch physicist Enrico Fermi famously asked: “If there is intelligent extraterrestrial life in the Universe – then where are they?” indicating that we have never met aliens or came across evidence of their existence, such as radio signals which would be proof of a technological society. We could pose that same question about time travelers: “If time travel is possible, where are all the time travelers?”

The question, known as the Fermi Paradox, is an important one. After all, if it were possible to travel through time, would we not have bumped into a bunch of observers from the future at critical junctures in history? It is unlikely to assume that they all managed to perfectly disguise themselves, without making any errors in the design of the clothes they wore, their accents, their vocabulary, etc. Another option is that time travel is possible, but it is used with the utmost care and tight control, due to all the dangers we discuss here.

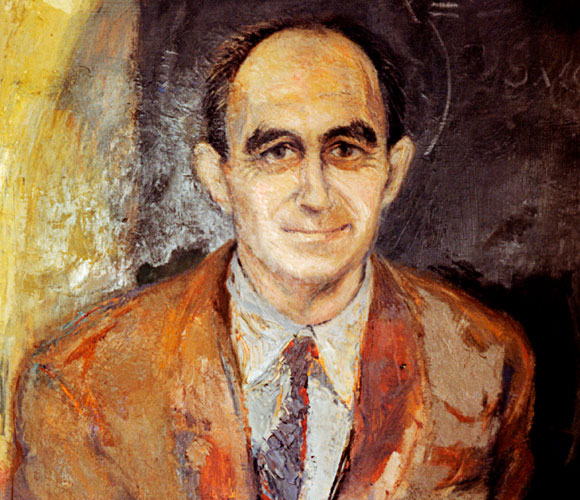

But where is everybody? A painting of the Italian physicist Enrico Fermi – Emilio Segrè Visual Archives SPL

On June 28, 2009, physicist Stephen Hawking carried out a scientific experiment which was meant to answer this question once and for all. He brought snacks, balloons and champagne and hosted a secret party for time travelers only – but sent out the invitations only on the next day. If no one showed up, he argued, that would be proof that time travel to the past is not possible. The invitees failed to arrive. “I sat and waited for a while, but nobody came,” he reported at the Seattle Science Festival in 2012.

Multiple time travelers also undermine the possibility of a fixed and consistent timeline, assuming that the past can indeed be changed. Imagine, for example, a nail-biting derby between the top clubs, Hapoel Jericho and Maccabi Jericho. Originally Maccabi won, so a Hapoel fan traveled back in time and managed to lead to his team’s victory. Maccabi fans would not give up and did the same. Soon, the whole stadium is filled with time travelers and paradoxes.

One way or round trip?

When considering travel, it is always continuous – from point A to point B, through all the points in between. Time travel should supposedly be the same: travelers get into their machine, push the button, and go from time A to time B, through all the times in between. But there’s a catch, if we are only travelling through time, then to the casual observer, the time machine continuously exists in the same space between the points in time. The result is that our journey is one-way and the time travelers will stay stuck in the future or the past because the machine itself will block the time-path back. And that is before we even start wondering how to even build this thing in the first place if it already exists in the place where we want to build it.

If that’s the case, then there’s no choice but to assume that there is some way to jump from time to time or place to place and materialize at the destination. How will our machine “know” to jump to an empty area, and to avoid materializing into a wall or a living creature unlucky enough to occupy that same spot? The passengers will undoubtedly need effective navigation and observation equipment to prevent unfortunate accidents at the point of entry.

While travelling from one point in time to another are passengers passing through all the moments in between? Good question! Photo: Shutterstock

Advanced time travel

In addition to the problems that time travel poses for anyone trying to keep the notion of cause and effect in order, time travelers may also face – or already have faced – other challenges from physics, even classical physics.

One issue you have to consider during time travel, and which science fiction writers usually prefer to ignore for convenience sake, is the question of arrival at the specified time destination and what would happen to us there.

It is usually assumed, with no good reason, that if someone is travelling through time, he or she will land in the same place, but at a different time – past or future. But this is where we hit a snag: the Earth rotates around the sun at a speed of 110,000 kph, and the Solar System itself is moving in its trajectory around the galaxy at a speed of 750,000 kph. If we time-travel for even a few seconds and stay in the same coordinates of space, we will probably find ourselves floating in outer space and perhaps even manage a quick glance around before we die. Our time machine will have to take into account this movement of the heavenly bodies and place us at exactly the right spot in space.

This alone may be resolved, since time travel, in any case, takes place between two points in the four-dimensional space-time continuum. According to the theory of general relativity, the theoretical foundation for time travel, space and time are a single physical entity, known as space-time. This entity can be bent and distorted – in fact gravity itself is an external manifestation of space-time distortion.

The Time Lord ,Doctor Who explains what “time” is exactly (Doctor Who, Season 3, Chapter 10: Blink).

Time travel would be possible if we could create a closed space-time loop, or if we could go from one point to another through a shortcut called a “Wormhole”. This would, in any case, not be just moving from one point in time to another, but would also include moving through space. Thus, from the outset, the journey is not only in time, but necessarily includes a destination point in space, which we will need to pre-program on our machine, of course .

In practice, the situation is more complicated – especially if we want to go into the distant past or distant future. The speed of the celestial bodies, and even the Earth’s shape and the structure of the continents, the seas, and mountains on the face of the Earth, change over the years. And because even a tiny deviation in our knowledge of the past can land us in the core of the Earth, in outer space or somewhere else that immediately reduces life expectancy to zero – time travel becomes a Russian roulette.

How to travel in time and stay alive

Let’s assume we coped with this problem and managed to get to the exact point in space-time that can sustain life. Careful – we’re not there yet; we still have to deal with momentum.

Momentum is a conserved quantity, which basically represents the potential of a body to continue moving at the speed and direction in which it is already travelling. If we were to jump out of a moving car (heaven forbid!), conservation of momentum is what would cause us to roll on the ground and probably get injured (in the best-case scenario). And so, if we leap in time – say, a month back – and land at the exact same point on Earth – we would discover, much to our dismay, that even if we started motionless in relation to the ground, now the ground underneath us is moving quickly at one angle or another towards us . Thus, even if we were lucky enough not to crash immediately on impact, we’re likely to hit some obstacle. And if by some miracle we were to survive, we would quickly find ourselves burning up in the atmosphere or gasping for air in space – because we have far exceeded the escape velocity from Earth.

We still have to deal with the issue of momentum in our time travels / Illustrative picture, Shutterstock

A possible solution to this problem is to plan our landing point ahead, so that the ground speed will be equal in size and direction to our exit speed, but this places many constraints on our journey. We could always leap into space, where there are hardly any moving objects to be bumped into, and only then land again at our point of destination on Earth.

Having said all that, this problem arises chiefly when we assume that time hopping is immediate – that we disappear from one point in time and immediately appear in another, without losing mass, energy, or momentum. But since a “realistic” journey in time is not instantaneous, rather it involves travelling along space-time, it is no different from other types of journeys. This being the case, we can hope that we could adjust our speed to the desired value and direction prior to landing, just like a spacecraft slowing down before landing on a planet.

We should also keep in mind that thankfully, we will have access to a powerful technology that would enable us to cope with such problems: Time-travel technology itself. For example, we might decide to send thousands of tiny probes ahead of us, each to a slightly different point in space-time. Some of them, maybe even most, will be destroyed for one of the reasons already mentioned. The others will wait patiently until the present and then feed their programmed coordinates into the time machine. Thus by definition, the destination entered will be safe for us, except, perhaps for the annoying probe shower hitting the travellers. For the travellers themselves, the entire process will be immediate.

Time Travelling Grammar

Finally, we come to the question: How do you actually talk about time travel? The three tenses – past, present, and future – are insufficient to discuss a future event that happened some time in the past with someone who is in the present, which is another’s past and yet another’s future. And what is the correct grammatical tense to use when we talk about an alternative future that would have been created after we killed our grandfather? Or how do we express the future-past tense (or past-future, or past-future-past?), when we get stuck in a time loop where what will happen leads to what had already taken place, and so on? And of course the biggest question that Hebrew editors and translators have faced for years – is there really such a thing as present continuous?

It’s complicated.

Arguing about tenses and a time machine, The Big Bang Theory, Season 8, Episode 5, 2014

In his book, The Restaurant at the End of the Universe, science fiction writer Douglas Adams suggests to his readers to consult (by Dr. Dan Streetmentioner) Time Traveler's Handbook of 1001 Tense Formations (by Dr. Dan Streetmentioner) to find the answers to these questions. That’s all very well, but, Adams tells us, “most readers get as far as the Future Semi-Conditionally Modified Subinverted Plagal Past Subjunctive Intentional before giving up; and in fact in later editions of the book all pages beyond this point have been left blank to save on printing costs.”

If, despite all of the above, you’re still intent on travelling back to Mount Sinai or the Apollo 11 moon landing – let us then wish you bon voyage, and please give our regards to Neil Armstrong!