Are modern collaborative workspaces negatively impacting workers?

It’s Monday morning. The alarm baby set itself to 5:00 am. Diapers changed, breakfast cooked, everyone dressed and ready, the baby safely dropped off at daycare, I finally set out to the office. En route, a sense of motivation builds within me - a fresh week brimming with possibilities. Arriving early, I find the office still empty. I delve into my tasks, ticking them off one by one. Soon, the space starts filling. Casual chatter to my left, a weekly assessment to my right. Seeking focus, I put on my headphones and immerse myself in preparing tomorrow’s presentation. My flow is interrupted by Shlomi from operations inquiring about an email I send. I return to my screen, but suddenly a birthday celebration kicks off for Ron, our secretary. On my way home, I find myself already counting the days down to Friday. Why does this narrative feel all too familiar, and what makes the workplace so utterly draining?

The Shared Office: Not as New as You Would Think

Studies show that the work environment has a profound influence on health, mood, employee performance, and more. One of the most common office layouts in recent years is the open plan office, also known as the ‘open space’. ‘Open Space Office’ or simply a shared office. In a shared space, workers occupy workstations not separated by walls, partitions, or cubicles. Despite its contemporary perception, this approach traces back to the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The transformations brought about by the Industrial Revolution led to accelerated growth in production and commerce, and with it an increase in the demand for tasks such as documentation, filing, marketing, etc. Offices were designed in the spirit of “Taylorism” - named after Frederick Winslow Taylor, an American engineer who developed the “scientific management” approach to maximizing employee output. Office workers were cramped into personal work stations placed in long rows in a spacious work area. Adjacent to them, managerial offices were established for those overseeing the junior employees. Taylor’s principles subsequently received harsh criticism and it was claimed that this work environment disregarded the employees’ needs for privacy, interpersonal communication, and more. The shared space became even less comfortable as technological advancements made work noisier, with typewriters clicking incessantly and telephones ringing from every direction.

After World War II, business owners could no longer ignore the need to improve the work environment. In Germany, which sought to distance itself from the first half of the 20th century by adopting new ideas, a new style of office design was developed in the 1950s, called “office landscape” (Bürolandschaft). Pioneered by two brothers from the Schnelle family, the sons of a furniture manufacturer, this approach aimed to dismantle the rigid arrangement of offices in rows and rows in the spirit of “scientific management”, dividing the workspaces into separate geometric shapes, arranged in a way that allowed flow, and separated by potted plants and curved partitions. Despite their seemingly random arrangement, these spaces were meticulously planned to promote interactions among employees with interconnected roles.

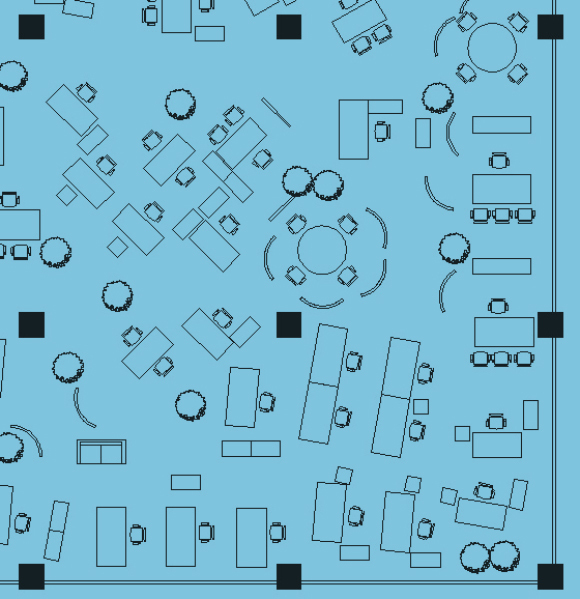

A workspace designed to facilitate seamless flow and forster meaningful interactions between employees. Classic office landscape plan | Newell Post, Wikimedia Commons

The introduction of the office landscape concept was met with enthusiasm in the USA, but not by all. Innovator Robert Propst, who headed the research division at Herman Miller (an office furniture company), argued that this design did not allow for the expression of talent and energy. He sought to transform the environment into a place that encourages innovation and productivity and enhances individual privacy. In 1968, after eight years of development, Propst launched the action office system for office space design, a design style that would influence office layout for at least the ensuing 40 years. The new design separated each employee’s personal workspace with three tall, adaptable partitions that could be opened and closed as needed. Initially, this design was praised, but company managers soon discovered that the partitions could be fixed in place, allowing a large number of employees to be crowded into the office space. Offices became “cubicle farms”. As a teenager in the 1990s, I vividly remember my astonishment at the portrayal of work cubicles in films such as “The Matrix”, “Fight Club”, and “Being John Malkovich”. I was dismayed at the thought that one day I might find myself confined to a work cubicle for a living.

I wasn't alone in feeling this way. Despite the privacy they afforded employees and the cost savings for employers, cubicles eventually became a symbol of isolation and disregard for employees' individuality. In his later years, Propst clarified that he had never intended for these cubicles to be so compact and numerous. The intense dislike for cubicles encouraged employers in the early 21st century to dismantle partitions and redefine the shared office spaces.

Today’s modern shared workspaces often boast aesthetically pleasing designs, featuring stylish seating areas and recreational complexes that encourage the employees to hang around for activities such as a table tennis tournament or a PlayStation duel. However, most companies opted for a simpler approach, adopting only the removal of partitions and seating employees collectively in a shared space, an even more cost-effective alternative to the cubicle farm. The concept of the modern “coworking space” is rooted in the belief that by coexisting in the same space, employees will naturally forge productive collaborations.

They saved employers money but became symbols of loneliness and disregard for the employees’ individuality. A cubicle farm | Illustration: Jesus Sanz, Shutterstock

The Coworking Space Impairs Communication between Employees

In practice, studies show that restricting privacy prompts employees to isolate themselves in the workplace. The magnitude of this phenomenon is evident, for example, from a field study conducted by researchers from Harvard University, which investigated employee behavior in a company before and after their transition from individual offices to coworking spaces. Over a mere three months, the surveillance system registered a 70% drop in face-to-face interactions, while the number of emails increased by 56%, and the number of SMS messages exchanged between employees increased by 67%. The researchers concluded that not only did the employees seek to avoid conversations that might disturb others in the coworking space but were also hesitant to appear as if they were wandering aimlessly around the office.

Delving into studies in organizational psychology, we discover that this paradox has been known for a long time. In 1980, researchers from the University of Tennessee explored the connection between office design and employee satisfaction. The researchers hypothesize that employees responsible for executing complex tasks requiring greater concentration would report higher work satisfaction in a quieter and more private workspace. Conversely, they expected those performing simple, repetitive tasks to appreciate the social environment of a coworking space. In reality, the researchers found that when employees’ workspaces afforded more privacy, their satisfaction increased, regardless of the nature of the work they performed. This same study also reported that employees in coworking spaces did not hold more interpersonal meetings, and those whose work stations were more isolated received higher ratings from management.

It’s easy to hypothesize why those employees were considered more successful. First, managers were less able to observe whether they were wasting time, and second, the open space provides visual stimuli - the continuous ebb and flow of colleagues, glimpses of other people’s faces and screens. Additionally, these dynamic surroundings come with a considerable auditory burden: conversations, ringing phones, clicking keyboards and more, all of which can hinder employees from effectively carrying out their tasks.

Restricting their privacy makes employees shut themselves in. Employees a shared space | Source: Monkey Business Images, Shutterstock

Does background noise necessarily disrupt productivity? Studies show that nearly everyone is affected by background noise to some extent, although sensitivity varies. British researchers inquired whether noises such as a ringing telephone, printer sounds, conversations and other sounds impede concentration at their work. Of those surveyed, 99% of employees reported that at least one of these noises slightly affected their concentration, while about 54% reported that a particular noise notably hampered their focus. Initially, the researchers hypothesized that over time, employees would manage to filter out the noise. However, they did not find a decrease in the level of disturbance among more experienced employees, and in fact found that the clicking of keyboards was more of a disturbance for more experienced employees.

Could it be that the work environment does not genuinely affect concentration, and people merely like to complain about their workplace? Recognizing that questionnaire-based studies can be inherently biased, researchers sought to quantify office worker performance. They focused on the Swedish Ministry of Transportation following the transition to an activity based work environment. These offices allow employees to choose between areas dedicated to different activities: a meeting area, a quiet space, a coworking space, a virtual meeting area, and more. The employees who participated in the study were invited to perform cognitive tests assessing the performance of their working memory in different work areas. Working memory is a short-term memory used for storing limited, accessible information required to perform cognitive tasks. For instance, when cooking, it helps us remember the number of eggs, cups of flour and cups of milk in a recipe and add them to the bowl without referring back to the cookbook. In the cognitive tests the participants were shown a series of numbers, which they had to remember and repeat accurately shortly afterward. Along with assessing memory performance, researchers also measured noise intensity in each workspace. The results indicated that when the intensity of noise was lower, the employees were able to store more items in their working memory. In quiet spaces, their performance was 22% better than in noisy areas.While working memory is not the only cognitive function we use during working, a significant disturbance in this area can slow down an employee, potentially costing the employer both time and money.

A shared work environment can affect concentration and health. A coworking space | Illustration: Anel Alijagic, Shutterstock

Privacy is Good for Our Health

The most alarming finding relates to our health, an issue that has drawn increased attention since early 2020. A survey conducted by the Danish government in 2011 on 2,400 office workers found a relationship between the number of employees sharing an office space and the annual number of sick days taken. Employees who shared their workspace with more than one other person reported almost double the average number of annual sick days taken compared to those in private offices. A Norwegian study that examined the number of workdays missed found that employees in a coworking space reported a 12% higher number of approved sick days than those who did not share their offices with others. This increase in illness is not surprising; everyone recognizes that an open workspace without partitions increases the risk of disease transmission.

Indeed, health concerns have catalyzed unprecedented changes in modern work environments. The COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent lockdowns prompted many workplaces to allow employees to work from home. Moreover, mechanisms for enabling remote interactions were improved and became routine, and employees became adept at collaborating without sharing a physical workspace. The big question is whether work from home is more productive or simply a way to avoid less comfortable office alternatives. The truth is that a coworking space often fails to achieve its primary goal - providing a comfortable place to work. Denis Diderot, the 18th century philosopher, coined the phrase “the fourth wall” - the imaginary barrier that separates actors from their audience, allowing them to ignore the audience’s presence. Similarly, employees in a coworking space often build their own “fourth wall”, erecting mental partitions to cope with the lack of privacy. In 2018, Panasonic launched its controversial product, Wear Space, designed to help people create such partitions. This wearable device limits sight and hearing like a personal office cubicle, reminiscent of horse blinkers that are designed to restrict the field of vision of horses in order to minimize distractions and help them focus on the track ahead. Will we see employees in the future wearing virtual masks that project an image of a luxurious private office with a city view from the 20th floor? Perhaps. Meanwhile, it may be wise to expand each employee’s personal space and create a quiet, considerate organizational culture.