A number of cases of the viral disease have been detected in the US and in Europe and health authorities are preparing for stopping it from spreading. The good news is there is an effective vaccine against it

A number of cases of monkeypox have been identified during the last few weeks in Western Europe and North America. The disease was first identified in Britain and during the last few days also in Spain, Canada, the United States, Portugal and Sweden. Global health organizations have raised concerns following the wide geographic distribution of morbidity, spanning a number of countries, due to fear of a scenario in which the virus will start circulating in populations outside of its normal area of distribution.

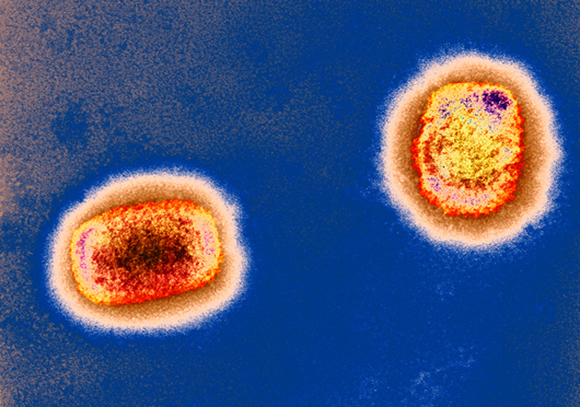

Monkeypox is a viral disease, prevalent mainly in Central and Western Africa, which causes the development of blisters all over the body. The disease is caused by a virus first identified in monkeys, even though they are not its main carriers. In the past, when the disease was detected in Western countries, its sources could usually be traced back to Africa.

Our monkeypox tracker is now live. It will be updated throughout the day: https://t.co/698WJtm1Qk pic.twitter.com/8Lnn0Wro7a

— BNO Newsroom (@BNODesk) May 20, 2022

Monkeypox cases tracker, updated by BNO Newsroom, as of the time of publication of this article

The virus is transmitted via bodily fluids, mostly through saliva, in large droplets emitted into the air. It penetrates through body orifices, mucosal tissues, and through wounds – including small wounds and broken skin that we may not even be aware of. The disease symptoms are somewhat similar to those of smallpox, which was eradicated in the late 1970s. Due to this similarity, there have been cases in the past in which monkeypox was misdiagnosed as smallpox.

The virus attacks cells of the immune system and following an incubation period of a few days, the characteristic blisters appear, along with high fever, chills, headaches and other inflammatory symptoms. Despite the familial and mechanistic resemblance, monkeypox is considered much less lethal. Although some findings indicate a significant mortality rate, reaching ten percent in Africa, from the more virulent variant, its hitherto rare occurrence makes it difficult to determine how dangerous it may be in countries with advanced medicine. Likely, it would be much less, especially since the current outbreak is of the second, less dangerous variant.

Studies which were conducted at the end of the previous century showed that the smallpox vaccine was also effective against other viruses of the same family, including monkeypox. In fact, the vaccine is actually based on a different virus of the same family, which causes only a mild illness in humans. In the past, it was once one of the routine vaccines given to children all over the world. Today, the vaccine is no longer administered since it is no longer needed – in Israel, for example, this vaccine was discontinued about twenty years ago. However, the protection provided by the vaccine abates after a few years, rendering unprotected both the vaccinated population and the population born after smallpox eradication. In the UK, vaccination has already begun for those who came into contact with monkeypox patients, in an effort to break the chain of infection at the very beginning. The UK has also begun to stockpile vaccines as a precaution, in case of a significant spread of the disease.

Monkeypox virus | Photo: UK HEALTH SECURITY AGENCY / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Is There Cause For Concern?

For now, there is no real cause for concern. The number of people identified as infected so far is very low – only a little over a hundred of verified infections throughout Europe and North America. It is likely that now, with the commencement of active monitoring of the disease, more cases will be discovered. According to one theory, the timing of the outbreak is related to the renewal of global tourist travel following the relaxation of COVID restrictions in most countries.

The disease is contagious, during prolonged face-to-face contact with a patient or by contact with blisters, bodily fluids or contaminated surfaces, such as clothing. The disease symptoms are very noticeable, especially the characteristic blisters, so that, in contrast to diseases such as COVID-19, it is easy to recognize a sick person and isolate him. However, patients become contagious with the onset of mild and early symptoms, even before the blisters develop, and some patients do not present with symptoms at all. The fact that patients have been detected in a number of countries simultaneously, could imply, in the worst-case scenario, that the virus has mutated and improved its human-to-human transmission ability, in which case there may be concern for human transmission and latent morbidity within the population.

Close monitoring of disease spread and rapid interruption of infection chains, along with maintenance of hygiene, could reduce the risk of the disease spreading. If the need for a more widespread action arises, there is also a safe and effective vaccine, albeit not free of side effects, which, in the past, was very successfully administered to billions of people. If necessary, there should be no difficulty in manufacturing and distributing it to outbreak areas.

So far, many of the patients are young adult males, with some being men who have sexual relations with other men. It is possible that the relatively high frequency of the disease in this specific group has to do with the lifestyle of some of the patients, as the virus may be transmitted from person to person during intimate or sexual contact, including prolonged skin-to-skin contact and exposure to saliva. It is worth waiting for additional findings, especially given that this is a known virus that comes from a family of viruses that has killed millions of people throughout history, but so far has not spread significantly.