Marking the 120th birthday of Amelia Earhart, the aviation pioneer who stretched the limits of humanity into the sky

Amelia Earhart saw an airplane for the first time in her life when she was 10 years old, at a family visit to a fair. Her father asked her if she wanted to ride it, but she was afraid and preferred to go with her younger sister to the carousel. Years later, Earhart described it as being “a thing of rusty wire and wood and looked not at all interesting.” Thirteen years would pass before her next opportunity to fly. This time it was an event that would change her life, and possibly the history of aviation.

A sister thing

Earhart was born on July 24, 1897, in a small town in Kansas. She was the first child of advocate Samuel Earhart, who married Amelia Otis, daughter of a former federal judge turned successful banker. The family’s house was on Amelia’s maternal grandparents’ estate, where she and younger sister Muriel grew up in the constant tension between the relatively liberal upbringing of their parents and the conservatism of their grandparents. The tension was reflected in a disparate approach to the girls’ education. While their grandparents thought the girls should be brought up to be “good girls,” their parents allowed them to climb on trees, play it rough with the boys, and even hunt for rats with a little rifle.

When Earhart was nine years old, her nuclear family moved to Iowa, following Samuel’s new position as a lawyer for a railway company. Amelia was home-schooled until the age of 12, and only then was sent to school for the first time. She was a good student who loved to read and found interest in science. Later on, her mother separated from her father, due to the drinking problem he could not overcome, moving with the girls to Chicago, where Amelia graduated from high school in 1915.

She later studied at a women’s college in Philadelphia, but left after a visit to Toronto exposed her to the many wounded soldiers returning from the battlefields of World War I in Europe, leading her to volunteer as a nurse's aide at the hospital. Her patients included many wounded pilots, their stories causing her to take interest in aviation.

In 1918, the Spanish flu pandemic reached Canada, making work at the hospital even more challenging. Earhart also contracted the virus and was hospitalized for a number of weeks due to complications, including pneumonia and severe sinusitis. Following her recovery, she turned to medical school in Columbia University, but left after one year to join her parents, who were back together, in California. There, during a visit to a fair in 1920, her father again suggested she should try flying a plane. This time she agreed. The flight was only ten minutes long, but it changed her life. “By the time I had got two or three hundred feet off the ground,” she said, “I knew I had to fly.”

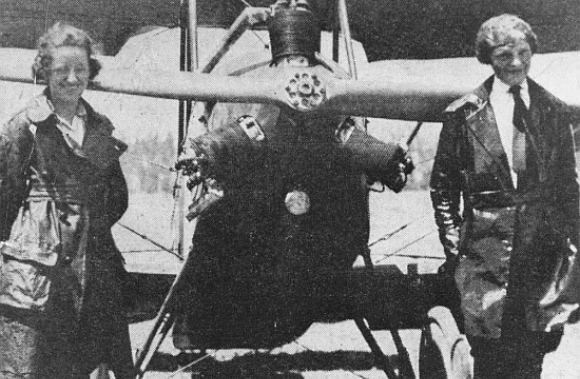

Early horizons. Eahart (on the right) and flight instructor Snook, in front of "The Canary"| Source: Wikipedia

A sack of potatoes

Earhart began her aviation training with pilot Anita Snook, one of the aviation pioneers in the US. During this time, she worked in every job she could find in order to save up money to buy her own plane. She was a truck driver, photographer, and stenographer at a telephone company, and in the summer of 1922, she bought a second-hand Kinner Airster airplane, nicknaming it “the Canary,” due to its yellow hue. After several of months, she already set the female pilot world record for flight altitude, reaching 14,000 feet. In 1923, she was the 16th woman in history to be issued a pilot's license by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale.

Soon enough, however, her aviation career spiraled into financial turmoil. Earhart's parents eventually divorced, and the mother and her daughters lived mainly on the grandmother's inheritance. When they ran out of money, and with no occupational future in aviation, she was forced to sell the plane. Earhart returned to her studies in Columbia, but had to drop out for financial reasons. She joined her mother in Boston, where she made a living by working as a teacher and social worker.

Nevertheless, the flying bug did not disappear. She served as a sales representative for Kinner Airplane & Motor Corporation in Boston and began writing articles about aviation for the local newspaper, which made her a well-known figure in the aviation community of northeast US.

In 1927, American pilot Charles Lindbergh completed the first solo flight across the Atlantic Ocean. His feat inspired many others to attempt the challenge, and Earhart was invited to be the first woman to fly across the Atlantic, even only as a passenger and not as the pilot. She welcomed the offer and on June 17, 1928, boarded pilot Wilmer Stultz and mechanic Louis Gordon’s plane in Canada. The three landed safely in Wales 21 hours later. In interviews after their return to the US, Earhart said “I was just baggage, like a sack of potatoes. Maybe someday I'll try it alone.”

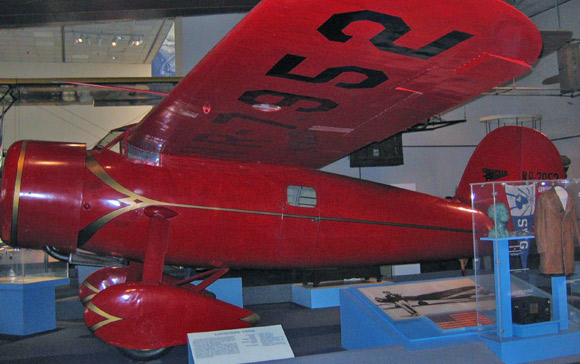

The plane in which Earhart crossed the Atlantic Ocean at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington D.C. | Source: Wikipedia

Spreading her wings

The three flight participants received a warm welcome upon their return, with a victory march in New York and a meeting with President Calvin Coolidge in the White House. Despite her limited role in the achievement, Earhart became a celebrity. Her status was partly promoted enthusiastically by publisher George P. Putnam, who was one of the initiators of the flight and connected her to his vast social circle. This included her appointment as an editor in Cosmopolitan magazine, where she wrote about aviation. She was also appointed vice president of a local aviation company. During this time, she participated in a number of flight competitions, and in 1930, was appointed the first president of the female pilot organization, the Ninety-Nines.

Earhart and Putnam denied rumors about an affair, but following his divorce in 1929, Putnam began persistently pursuing her until they married in 1931, after he promised not to hold her to “a medieval code of faithfulness.”

Around the time of their wedding, they began planning Earhart's solo flight across the Atlantic. On May 20, 1932, the fifth anniversary of Lindbergh’s flight, Earhart took off from Harbour Grace in east Canada in a Lockheed Vega 5B plane. Strong northern winds, an accumulation of ice, and mechanical problems prevented her from reaching Paris. She was forced to look for an alternative landing point, and after nearly 15 hours, landed in a field not far from Londonderry in Northern Ireland.

Her success made her a household name and won her many awards; among them were the Gold Medal of the National Geographic Society from President Herbert Clark Hoover, the Distinguished Flying Cross from Congress, and the Cross of Knight of the Legion of Honor from the French Government. In the years to come, Earhart continued to go out on daring flights. She flew solo from Hawaii to California and was the first person to cross both the Atlantic and the Pacific Oceans. She was also the first pilot to fly solo from Mexico City to New York. By 1935, she had broken seven aviation records for women, when she decided to take on the biggest challenge of all: to be the first woman to circumnavigate the globe.

A promise not hold her to “a medieval code of faithfulness.” Earhart with George P. Putnam | Photograph: Science Photo Library

The end of the road

Earhart was not the first pilot to fly around the world. A crew of American pilots did it in 1924, in a series of flights lasting 175 days. In 1929, Australian pilot Charles Kingsford Smith completed one lap around the Earth in a long series of flights, including the first crossing of the Pacific Ocean with a flight to Australia. Nevertheless, Earhart wanted to be the first to circumnavigate the globe taking the longest route, as close as possible to the equator.

In 1935, she joined the Aeronautical Engineering department at Purdue University as an advisor and a special counselor to female students. As part of the agreement with the university, it funded the plane for the mission, the Lockheed Electra 10E, which was built especially for that purpose, with most of its body being used for auxiliary fuel tanks.

Earhart formed a crew of two skilled navigators and a stunt pilot, who served as a technical advisor for the mission. The plan was to fly west, and in March 1937, the crew took off from Oakland, California to Hawaii. Several days later, the plane crashed during take-off in Hawaii, after it hit a ground loop on the runway in Honolulu, with no certainty if the cause was pilot error or a mechanical problem. No one was injured, but the plane suffered severe damage and was returned to California for extensive repairs.

For the second trial, a few weeks later, Earhart decided to fly east. Two crew members had to pass on the adventure due to prior engagements, leaving her and navigator Fred Noonan. They took off from California to Florida, from there continued to South America, crossed the Atlantic to Africa above the equator, and flew east through northern India, Indonesia, and northern Australia. At the end of June, they landed in Lae, New Guinea, after passing 35,000 km, with only 11,000 km remaining to fly across the Pacific Ocean.

The next stop on their track was the tiny Howland Island, 4,100 km away. Earhart and Noonan knew it would be very difficult to locate the small and flat island, which is less than two kilometers long and only half a kilometer wide, especially in cloudy conditions. They coordinated in advance a radio connection to a US Coast Guard ship anchored on the coast of the island, with the intent of using the ship's crew as a navigational aid.

The plane underwent additional renovation in Lae, removing any redundant item to reduce weight and save on fuel for the challenging flight. On July 2, 1937, the two took off. Problems emerged immediately after takeoff, and witnesses said the plane’s radio antenna broke. They encountered cloudier weather than expected, even though the forecast was clear. And, as if that was not enough, it was later found that their maps were outdated, showing the island 10 km from where it actually was.

On the morning of July 3, Noonan and Earhart contacted the ship, but the radio signal had many interferences, so it was not clear if they could hear the directions given by the ship’s crew. Just before 8 am, the crew attempted to provide radio directions, and even sent smoke signals, to no avail. The plane had probably ran out of fuel and the two were forced to abandon it over the ocean. The ship immediately set to find them, with additional aircraft and ships joining the search soon after, as instructed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Two weeks later, the search was discontinued, but Putnam decided to fund it for longer – with no success. No remains were found. In January 1939, a California court declared Earhart dead.

One of the most prominent figures in aviation history. Earhart on board a US Department of Commerce plane | Source: Science Photo Library

A role model for gender equality

Earhart and Noonan’s disappearance spawned a wealth of conspiracy theories. These included the claim that she crashed the plane to commit suicide; or that her real mission was to spy on Japanese forces in the Pacific for the US government. According to one theory, the two were captured by the Japanese and Earhart became Tokyo Rose – an unidentified English-speaking radio broadcaster who led Japanese propaganda broadcasts aimed at demoralizing the WWII American troops in the Pacific. A recent film, released on the 80th anniversary of her disappearance, displays so-called evidence that Earhart died in the Japanese prison.

A more feasible hypothesis regarding the pair’s disappearance is that the plane sunk into the ocean after it ran out of fuel, a few dozen kilometers from Howland. Another hypothesis suggested that the two landed by mistake on Gardner Island, an uninhabited island a few hundred kilometers away from Howland, which now belongs to Kiribati and is called Nikumaroro. An expedition to this island revealed aluminum pieces and a plastic window that may have belonged to their plane, as well as a few improvised tools, but no remains were identified with high certainty and no human body remains were found.

In 2014, a team of experts in aviation history determined that the piece of metal found on Nikumaroro in 1991 was indeed a part of Earhart's plane, but these conclusions still do not fully settle the 80-year-old mystery. In the 1970s, Earhart was claimed to be living under an alias in New Jersey, a claim which was finally debunked when National Geographic experts closely analyzed and compared pictures of the two women.

To this day, Earhart is remembered as one of the most prominent figures in aviation history. Numerous institutions and landmarks are named after her – from schools and educational institutions, through streets and bridges throughout the US, a dwarf planet, and a US Navy cargo ship. Purdue University and many other institutions have named scholarships they award after her, and her portrait has appeared on postal stamps, as well as in a museum established in her birth city. In addition, many documentaries and feature films were made about her.

But most importantly, through her personal story, Earhart has inspired many who were drawn to aviation, and serves as a role model for numerous women who worked to achieve equality in professions and fields considered “masculine.” Over a thousand female pilots followed her lead and volunteered to the US Air Force in WWII, serving as training and cargo pilots. Many other women, in aviation as in other fields, sought to walk in her footsteps and were inspired by her success. Amelia Earhart has proven that when it comes to wisdom, audacity and will power, women are not only equal to men, but can also surpass them.

Translated by Elee Shimshoni